Paul Klee is one of the most philosophical painters of the twentieth century. Although he seldom spoke of his work thinking that it is the task of the critic and not of the creator, he did not avoid the written word, in fact in 1906 he wrote in his diaries (1898-1918) : “I have succeeded in directly transposing ‘nature’ into my style.”1 He was then 27 years old. He added: “I have succeeded in maintaining my style in the immediate presence of nature.”2

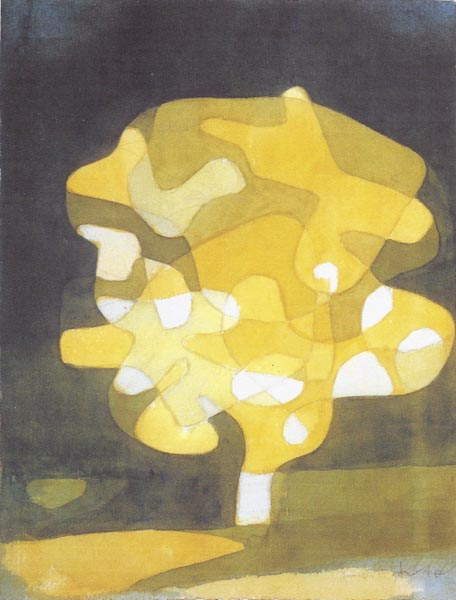

What is this style then? Style, briefly defined, is that which makes an artist recognizable among many others. But it could also be a school of painting, like cubism, for instance, a style that makes it difficult to distinguish easily a Picasso from a painting by Braque. Even so, Klee also wrote a Theory of Modern Art where he mentions with great clarity and determination that creativity is ultimately a mystery.”3 This conviction is nevertheless an invitation to explore Klee’s paintings and to admire in silence his works of art. His style stresses the relevance and importance of the line and the point; Klee is a linearist who remains a linearist to the end, especially so when he enriches his lines with painted objects: trees, human figures or not-so- human figures. These lines can be vertical, horizontal, or diagonal which combine together virtual horizons, and which, if the eye follows them, lose a unique, defined point of reference. Since Klee’s lines are suddenly interrupted they give the impression of having been drawn consecutively; the eye that perceives them wanders in different directions trying to find continuity, an illusory continuity that is virtual and yet actual. I can give the example of a tree painted by Klee in 1920 [figure 1]. At first it looks so simple, yet, if we try to copy it we find ourselves in a web of difficulties: the copy is most likely not a duplicate but something only resembling the original.

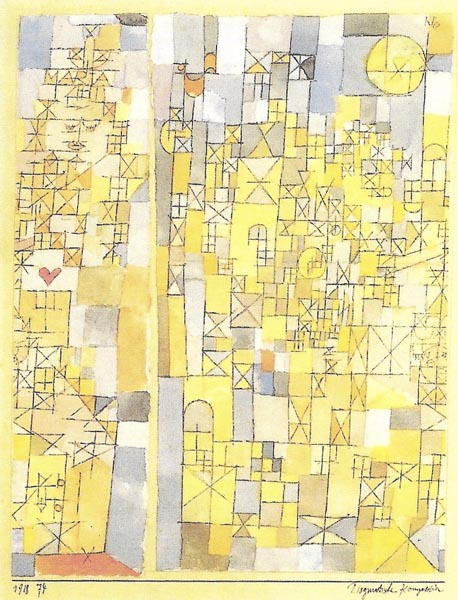

Klee refused to say that his paintings were products; to use that word would put his art in the category of utensils or gadgets, tools produced industrially and not artworks deserving the name of masterpieces. One of the most fascinating things about Klee’s art is that he did not limit himself to drawing intricate webs of lines. He added, especially in his mature works around and after 1912, layers upon layers, inserting additional figures: tress, flowers, and human figures to a linear background. Partially influenced by cubism, he went beyond the strict rationality of that style of painting, he even painted in 1918 a caricature of that style calling it Dogmatic Composition [figure 2]. Indeed Klee was not afraid of expressing the witty and ironic side of his personality; comedy was not extraneous to him, he even drew a piece of furniture to which he gave the title “Caricature of a piece of furniture”. This apparently simple title shows how Klee’s creative vein never tired of combining the most disparate visible objects and categories (such as ‘caricature’) that were never associated before in that manner.

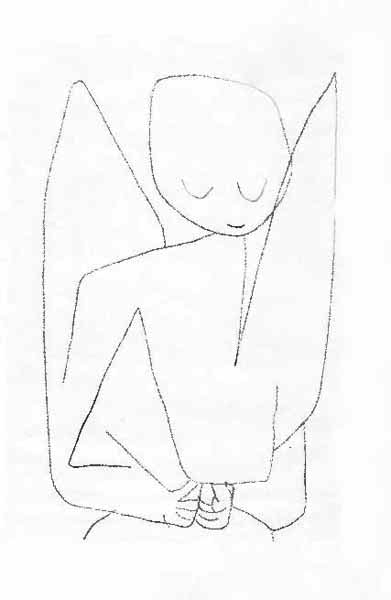

There is another point I would like to make before concluding, and that is the well known fact that Klee had a penchant for angels. One such painting, Angelus Novus of 1920, was commented upon at length by Walter Benjamin, but it must also be said that Klee in his later years drew many of such angels with “simple” pencil lines. They are witty not only when just looked at, also their titles elicit a smile, since they are not always “appropriate” while thinking of angels. “Angelus Dubiosus”, “Unfinished Angel” or, to add a few more: “Forgetful Angel” an angel who looks shy, with his eyes closed, and finally: “Precocious Angel” drawn in 1939 [figure 3].

Why this inclination toward angels? I venture to say that when Klee said that he was painting for the unborn, he was thinking about angels, these creatures who are neither gods nor humans; maybe he thought of them being the creatures who will inherit the earth, considering that Klee gave to his drawings of angels an almost down-to-earth appearance. If human beings are imperfect, angels imitate them or, maybe, human beings imitate angels, a new and different form of life out of which Beauty is born.

Figure 1. Fig Tree

Figure 2. Dogmatic Composition

Figure 3. Forgetful Angel

Marcella Tarozzi

New York, 2013

Bibliography

- The Diaries of Paul Klee—1898-1918 Edited, with an introduction by Felix Klee. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1992.

- Paul Klee, Théorie de l’art moderne. Translated by Pierre-Henri Gonthier. Paris: Denoël, 1985.

- Paul Klee–The Angels. Edited by Zentrum Paul Klee. Bern: Hatje Cantz, no date.

Notes

The Diaries of Paul Klee—1898-1918, ed. Felix Klee (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1992), p. 197.

Ibid., p. 196.

Paul Klee, Théorie de l’art moderne, trans. Pierre-Henri Gonthier (Paris: Denoël, 1985), p. 57.

Apeiron Centre, 2013